Country, language, love, wonder: new picture books to enjoy.

This is another ‘picture book bounty’ post, with four picture book arrivals to share.

I have introduced Gumbaynggirr artist Melissa Greenwood’s work in earlier posts with her beautiful books in which her First Nations language sits side by side with English as she writes and paints about the world. Darruyay Yilaaming Marraala, Buwaarr (Welcome to the World, Little Baby) is just as lovely and also a little different: it is presented as a baby book, in which proud parents, grandparents, aunties, uncles or other important adults in a child’s life can record features of the birth, special memories, family, Country, relationships, and baby’s developmental milestones. It’s designed for First Nations families but not exclusively so. A very welcome addition to a tradition of baby books.

Published by ABC Books imprint of HarperCollins in March 2025.All the Ways Mum will be there for You by Sarah Ayoub is another celebration of love between parent and child. This one features an array of mums and kids going about busy days and evenings, sharing adventures, quiet times, special moments together. The vibrant colourful illustrations by Kate Moon add to the scenes and little ones can put their own imaginative minds to work as they turn the pages.

Published by HarperCollins Australia & NZ in February 2025.The World Needs the Wonder You See by Joanna Gaines is a reminder to us all, young and old alike, to slow down and take notice of the world around us – something we often forget to do in the busyness of the modern world. It’s a North American setting so Aussie kids will see bunnies, foxes and squirrels cavorting in meadows and forests, with a fair bit of anthropomorphism going on, but it makes for a magical world that young kids will relate to, perhaps akin to the world of Winnie the Pooh and the Hundred Acre Wood. Julianna Swaney’s illustrations provide detail and variety to engross small viewers.

Published by Tommy Nelson in the US, an imprint of HarperCollins, in January 2025.Finally, Learning Country: A First Nations Journey Around Australia’s Traditional Place Names by Ryhia Dank, takes small readers to some well-known places in Australia, describing them by their traditional names and the stories told by the Old People. We visit Boigu in the Torres Strait, Canberra, Meeanjin (Brisbane), Narrm (Melbourne), Boorloo (Perth), among others. Ryhia is a Gudanji/Wakaja artist from the Gulf of Carpentaria and has illustrated the book with vibrant contemporary artworks that bring to life the stories she has chosen to tell about the traditional names of Australia.

Published by HarperCollins Australia & NZ in June 2025.My thanks to the publishers for copies of these books to review.

Nurturing peace: ‘The holy and the broken’ by Ittay Flescher

Since the Hamas attacks on Israel in October 2023 and the resulting devastation of Gaza by Israeli defence forces since, I have been silenced. How could I put into words my revulsion at the violence, my despair at the apparent intractability of the centuries-old enmity? I knew too little about the history of the conflict, the bewildering tangle of geo-political and religious factors that have contibuted to the bitterness poisoning generations of Israelis and Palestinians.

Many of my left-leaning friends and contacts were vocal in their criticism of the Israeli government for the brutality of the retribution wreaked on innocents in Gaza, including women, children, the elderly, the sick. I could not disagree with this. Bombing hospitals, denying medical and water supplies to civilians surely can never be justified.

But the chant at ‘pro-Palestinian’ rallies of from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free – what does that mean? That the Jewish population should be expunged from the land? To go where? And then?

When I saw Ittay Flescher’s book title and subtitle, I knew I had to read it. The holy and the broken references a line from Leonard Cohen’s beautiful song ‘Hallelujah’, which Flescher argues would be Jerusalem’s anthem if she were a soundtrack rather than a city. As a place of deep and abiding significance for three of the world’s major religions, Jerusalem and the land that surrounds it is certainly holy. But torn apart over centuries by ancient battles, crusades and modern warfare, it would be difficult to argue that it is not also broken.

And the subtitle: A cry for Israeli-Palestinian peace from a land that must be shared positions both the book and its author from within the land in question, not a book written by an outsider, but by someone intimately familiar with the land and its people. And importantly, someone who believes that the way forward is to imagine a different future for both Palestinians and Israelis.

The author is someone who has worked as a peace builder and educator for many years, both in Jerusalem as the education director at Kids4Peace, an interfaith youth movement for Israelis and Palestinians, and as a high-school educator in Melbourne.

His book opens with a personal account of the October 7 Hamas attacks from the perspective of an Israeli man in Jerusalem: hour by hour, then day by day, both absorbed and repelled by what he was seeing and hearing on the news, wanting to turn away but also needing to know. Seeing his country become instantly united by this existential threat; opposition to the government seemingly shut down overnight.

Then he draws back and begins to reflect and to question.

In Flescher’s view, the core of the tragedy between the river and the sea is a deep and reciprocal misreading of the other. Here he touches on education, media and journalism, language difference, even religious texts: all can play a part in either cementing difference and stereotypes, or affirming the humanity of everyone who lives there.

All have suffered historic and ongoing trauma. Palestinian and Israeli families experience daily pain and heartache at the loss of loved ones in senseless acts of violence. Their religious traditions feature deep, historic connections with the same land.

He emphasises the importance of building grassroots connections across religious and language divides; the kind of connections that occur outside political structures. Take the politics out of it; the people who have the most to gain from peace are youngsters, their parents, friends and neighbours. People who just want to get on with their lives.

It involves recognising each other’s humanity, and understanding that the love Palestinian and Israeli parents hold for our children is the same, as is the profound grief we experience when they are taken from us.

It means embracing the notion that injustice anywhere poses a threat to justice everywhere and that security of one side requires security for the other.

The holy and the broken pp 222-223The most moving section of the book for me was found in the two letters the author wrote to future Israeli and Palestinian teenagers, which come towards the end of the book. They beautifully encapsulate his vision for what the land he holds so dear could be like, ‘when there is peace.’

If, like me, you have been at a loss as to how to think about or discuss the Palestinian/Israeli conflict, or wish there was an alternative to the black-and-white rhetoric of much of the public debate on the issue, I urge you to read this book. It offers another perspective and a welcome glimmer of hope on an otherwise very dark horizon.

At the time of writing this post, the author has planned a number of book launch dates in Australia. I am going to the Sydney one. Perhaps I will see some of you there.

For more information about Ittay, his book or his lifelong work for peace, you can visit his website here.

The holy and the broken is published by HarperCollins in January 2025.

My thanks to the publishers for a review copy.More Australian history adventures for kids: ‘Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger’ by Jackie French

I’m delighted that my final book review post for 2025 is another brilliant historical fiction for middle-grade readers by Jackie French. Did I mention I am a fan? Maybe once or twice…

The reason is that she effortlessly tells stories about Australia’s past that ignite imagination and a passion to know more, wrapped up in tales of adventure featuring characters we can both admire and relate to.

Tigg is such a character. Growing up an orphan on the fringes of the rough and dangerous Victorian goldfields of the 1850’s, Tigg has had to learn many things to survive. Under the less-than-careful eye of ‘Ma Murphy’ who runs a shanty on the diggings but gambles and drinks most of the takings, Tigg has learnt how to grow vegetables from her neighbour, a Chinese gardener; bush skills from Mrs O’Hare, a Wadawurrung woman; and reading and writing from ‘Gentleman Once’, who used to be a teacher at a grand school for English boys.

She has also learnt how to be a bushranger.

Disguised as a boy, she holds up coaches on the way to and from the diggings, but only ever takes half of passengers’ money, and never anything precious like a wedding ring. And she only robs to get money so that Mr Ah Song can pay rent for the land he gardens.

But one day everything goes very badly wrong and Tigg has to go into hiding, until a plan can be hatched to smuggle her out of danger – disguised this time as a Chinese man on his way to the goldfields. To do this, she must join with hundreds of other desperate, poor and hungry Chinese on what became known as the ‘Long Walk’, a journey across unmarked territory of hundreds of miles, facing thirst, hunger – and attacks from angry white men and sometimes even children.

So the author weaves in another of the astonishing stories from Australian history; one that has until relatively recently been hidden or forgotten. The shameful racism directed specifically against Chinese people which reared its ugly head during the gold rush period of the mid 1800s. It persisted for decades, manifested in the so-called ‘White Australia Policy’ of the early 1900s and, it could be argued, rose again with politicians like Pauline Hanson seeing an opportunity to score points on the back of anti-Asian sentiment.

The power of Jackie French’s writing for children is that she is not afraid to introduce these topics for younger readers. She treats her readers with respect, knowing that children can learn about difficult things that have happened in the past and reflect on how they have impacted on the present. Seeing the nineteenth century world of colonial Australia through the eyes of someone like Tigg allows a perspective other than our own, like putting on a magic pair of glasses or stepping into a time machine. Tigg grows up in an environment of poverty, deprivation, surrounded by racists and opportunists – but also by people of many races, and people of generosity and kindness. In other words, people.

Towards the end of the novel, Tigg discusses the appalling attacks she has witnessed with a businessman she comes to know, hoping he can do something to help:

‘You’re a wealthy businessman. I want you to convince the colonies’ parliaments to welcome the Chinese into Australia.’

He looked at her, amused. ‘I am afraid that is beyond my ability.’

… ‘Why?’ demanded Tigg. ‘The Chinese here are peaceful and hard-working and have skills the colonies need.’

‘None of which matters in the slightest. The Chinese look different, and that is enough. Starving miners need to think there is at least one class more miserable than themselves, and so they choose the Chinese, or indeed any Asian to look down on, be afraid of, or hate. Don’t you have a slightly easier request?’Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger pp277-278

So we go into Tigg’s world, not wanting to put the book down when it’s lights out time or we are tired. We want to keep reading because we care about Tigg and all the other amazing but believable characters around her.

Jackie French’s novels can do that. They are magic.

Tigg and the Bandicoot Bushranger is published by HarperCollins Childrens’ Books in December 2024.

My thanks to the publisher for a review copy.Memory lane: ‘Dropping the Mask’ by Noni Hazlehurst

My son spent a portion of mornings and afternoons in his early childhood, enjoying the company of Big and Little Ted, Jemima, Humpty, the square and round windows – and Noni Hazlehurst, among a cast of other beautiful and engaging presenters and characters. PlaySchool was a ground-breaking progam when it began on the Australian Broadcasting Commission in the 1960s and is still the longest-running children’s TV show in Australia.

The show’s guiding philosophy is about respect for children, kindness, familiarity along with new experiences, and a simple approach that ignites imagination rather than dictates what young viewers should think and feel.

Perhaps unsuprisingly, these qualities have been reflected in Noni’s own approach to life and to her many roles in TV, film and theatre.

Dropping the Mask is her story: from a sheltered childhood in suburban Melbourne, to attending the drama school at Flinders Univeristy in Adelaide in the heady times of the early 1970s, her first steps into the world of performance, a successful acting career, and the inevitable ups and downs of any life lived well.

The book follows a fairly straight chronology, with asides here and there where Noni reflects on experiences and draws out her themes, the main one of which is about living an authentic life rather than ‘pretending’ (kind of ironic if you think about how acting is perceived by most viewers). The motif of the mask appears often. Noni’s view of performance is that when inhabiting a dramatic role, she has always felt able to be her most authentic self, drawing on her own experiences and emotions to present the truth of a character, rather than simply performing the words of the script.

There is so much I loved about her story. I was born at the tail end of the ‘baby boom’ era, but with two older sisters I recognised so much of Noni’s experience as a youngster: the conservatism of Australian society and politics at that time; the emergence of teen culture and the more radical ideas coming from the UK and USA; the rampant growth of consumerism; the agonies of the teen years; memories of the 1969 moon landing; the beginnings of genuine multiculturalism. I know the feeling of suddenly becoming, in effect, an only child when older siblings leave home. I remember starting university and the realisation that there was a whole world of new thoughts and ideas to experience.

For fans of film and stage, Noni’s many reflections on the growth of Australia’s movie, TV and theatre industries are fascinating. There are some anecdotes from behind the scenes – some startling, some very funny.

She describes the joys and challenges of family life while trying to balance an acting career; her experiences living in the Blue Mountains of NSW and Tamborine Mountain in Queensland; the sad fact that the arts in general appear to be held in higher esteem in other parts of the world than in Australia.

Among the masks that Noni has observed in her life were those worn by her parents. Even as a child, she always had a sense that they were ‘acting happy’, that things were not quite right. Their world was tiny, protected, safe, with a small circle of friends from church. Her mother seemed anxious, her father very protective. It was not until after their deaths, when Noni appeared on an episode of the Australian version of the TV family history show Who Do You Think You Are? that she understood why.

Even if you are not a regular fan of the show, this episode is definitely worth watching. Seeing Noni realise how her newlywed parents’ WWII experiences in England created enduring emotional legacies for their family, is very moving. And the show’s other revelations about the long family history of performance artistry are incredible.

Dropping the Mask was for me, rather like enjoying a long conversation with an old friend about family, life, the choices we make, and the things that are important to us. Highly recommended.

Dropping the Mask was published by HarperCollins in October 2024.

My thanks to the publishers for a review copy.The fight for the vote: ‘An Undeniable Voice’ by Tania Blanchard

I have always felt a certain pride that Australia was one of the first countries (after New Zealand) to allow (white) women to vote. And puzzled by the slowness of Britain to do the same. Was it because of centuries of entrenched attitudes in Old Europe – attitudes towards women and men, and their relative roles in social, economic and political spheres? After all, many of those attitudes were transplanted to the Antipodes, along with convicts, rabbits and a cornucopia of noxious weeds. So why did Britain lag so far behind us before bestowing on half its population the basic democratic right to vote for their representation in government?

An Undeniable Voice traces the long-drawn-out fight for women’s suffrage in Britain. It’s a follow-on from an earlier novel by Tania Blanchard, A Woman of Courage, which I have not read – and I found that it reads perfectly well as a stand-alone.

It is 1907, and we meet Hannah Rainforth, an active member of her small northern colliery community in England. She and her husband run the pub she inherited from her parents, which she has turned into a kind of community hub, a meeting place for people to come together for various groups and projects, and support when times are hard.

But when her husband dies suddenly, Hannah is left with three children to support, and comes face to face with the inequalities experienced by women in all spheres of life: in marital laws, property, finance and employment. She knows that nothing will change unless all citizens are entitled to vote for those who make the laws that affect them.

Hannah has to make some hard decisions when she loses the right to continue as publican: moving to London, she returns to her teaching career but must leave her two sons to do so. Working to regain her old life and reunite her family, she also throws herself into the suffrage movement.

The narrative gives a comprehensive and compelling account of the activities of those working for women’s suffrage: from polite petitions to smashing windows, from peaceful marches and deputations to imprionment and hunger strikes. The brutal treatment of women on the streets and in prisons at the hands of police, government spies and prison guards is hard to read at times. What were these men so afraid of? Obviously the thought of losing their tight grip on the reins of power drove their violent and at times, bizarre responses.

Some readers may be surprised at the historical facts highlighted in this novel: that even for men, ‘suffrage’ was not then universal. There were property qualifications that attended the right to vote. In other words, men had to own a certain value of property before could register to vote. How much harder was it for women, then, when there were barriers for women owning property or taking out a loan in their own right?

The struggle for women’s suffrage took much, much longer than it should have in Britain. It was not until the ravages of WWI so thoroughly shook the nation that it was impossible for things to return to the old ways, that true progress began to happen.

In those long years, Hannah and her compatriots risked and suffered a great deal.

We all owe these women, and the men who supported them, a great deal.

An Undeniable Voice is published by HarperCollins in October 2024.

My thanks to the publishers and NetGalley for a review copy.

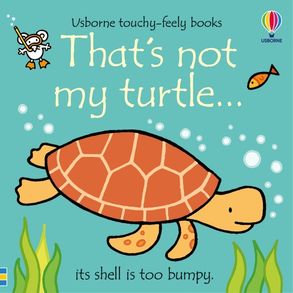

Touchy-feely: ‘That’s Not My Turtle!’ by Fiona Watt and Rachel Wells

If you have ever had anything to do with sharing a book with a very young baby or child, chances are you’ll have come across one or more of the Usbourne ‘Touchy-feely’ series of board books.

Title include That’s Not My Kitten, That’s Not my T-Rex, That’s Not My Teddy, That’s Not My Tractor, That’s Not My Elephant… you get the idea.

Each sturdy little book features aspects of the creature or object in question, with tactile cutouts on each page allowing small fingers to experience the various parts that don’t measure up.

In this case, it’s the turtle’s flippers that are too scaly, the tail too rough, the eggs too smooth…until on the last page, the correct turtle is identified by its shiny tummy.

Along with the tactile features, the repetition of the format in the series, and within each book, allows little ones to anticipate and participate in the story.

This new title will sit happily alongside its Touchy-feely brothers and sisters in the book basket or on the shelf. They are cute, affordable and (almost) indestructible little books that tiny people will love.

That’s Not My Turtle is published by HarperCollins Children’s Books in September 2022.

My thanks to the publishers for a review copy.